How the federal government created the immigration crisis that now bedevils it

The U.S.-Mexico border is once again one of the most momentous issues of the election season.

With immigrant crossings at their highest levels in decades, Republicans are running on the issue of a border in “crisis” — language once considered hard-line that’s been increasingly adopted by President Biden himself.

Now, with many voters citing immigration as their top concern heading into November, Congress has wrangled with — and scrapped — a sweeping border policy deal that would have drastically reduced the ability of migrants to claim asylum.

The mounting concerns and clamor for reform that engulfed the Senate for months didn’t come out of nowhere: They stem from past legislative rushes that built the current immigration system and the situation at the border.

Election-year decisions

In 1996 and 2006, Congress passed the last significant border and immigration bills to date. Both were hawkish messages to voters in election years, and both have become infamous for their unintended consequences.

The current rise in crossings stems from “a self-inflicted injury,” according to Denise Gilman, who directs the Immigration Clinic at the University of Texas at Austin.

“This is a crisis because we’ve made it a challenge to process these folks,” Gilman said, arguing that decades of punitive border policy had forged a political controversy out of what was once a run-of-the-mill administrative question: how to process people entering the country without a visa.

Starting with the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) in 1996, Gilman said, Congress “created a system that created a huge draw of resources — when [it] could have created a system that was much more humane and just and fair.”

The story of that past legislation offers insight into how the border went from a fringe issue to a central political concern in just a few years — a shift also marked by the fading away from the mainstream debate of once-standard immigration reform planks such as a “path to citizenship.”

That legacy also offers a cautionary tale of how any new reforms could impact — and worsen — the already ailing U.S. immigration system for decades to come.

“We have seen what happens when Congress moves immigration bills without sufficient input from critical stakeholders, including immigrant communities and those who represent them,” said Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), who was a member of the House in 1996 and was appointed to the Senate months before approval of the Secure Fence Act of 2006.

“I voted against both IIRIRA and the Secure Fence Act because I believed then, as I believe now, that immigrant families most affected by these policies and elected officials that represent these communities must be a part of shaping our immigration laws.”

At the time, Latino underrepresentation was the determining factor in excluding those representatives from discussions — the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC) didn’t have the numbers and clout it has now.

“Latino underrepresentation in Congress was a capital-P problem then in a way it isn’t now,” said Dara Lind, a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council.

But the 2023-24 Senate border negotiations excluded CHC members while focusing on border policy with only minimal elements of immigration reform.

How the border got militarized

Back in 1996, the IIRIRA’s legislative process was substantially different from this week’s dead-on-arrival Senate deal’s, but the political incentives to come up with legislation — any legislation — were similar.

“When you have a desire to pass a bill on immigration in an election year, you give up a lot of negotiating leverage if you’re the incumbent president. And that means that you can’t then really stand on principle on a lot of stuff because you’re already out there publicly saying you want a deal to get made,” Lind said.

The IIRIRA came about from a series of opportunistic moves by federal lawmakers and administrators — moves that helped create a sense of self-reinforcing crisis in many ways analogous to today, experts told The Hill.

In 1993, faced with complaints by El Paso residents annoyed by migrants moving through their Texas city, a local Border Patrol commander launched Operation Blockade — a highly popular move that President Clinton followed with Southern California-based Operation Gatekeeper in 1994.

In the narrow sense of keeping migrants out of San Diego and El Paso, the operations were a success, said Douglas Massey, who studies the sociology of immigration at Princeton University.

But in a broader sense, by “militarizing” the two biggest border crossings, the federal government diverted the flow of job-seeking migrants into more sparsely populated areas.

“And then that creates this new issue of massive numbers of people crossing the border of Arizona,” Massey said. When it was 30,000 people per week entering into a metropolis such as San Diego, they were relatively inconspicuous, “but that many people crossing in Douglas, Ariz., makes a big impression — and creates the impression that the border crisis is out of control.”

More border enforcement had another potent effect that lasts to this day: The more officers deployed to the border, the more migrants they were in a position to find — creating the often-false impression that migrant numbers were increasing.

From ‘immigration reform’ to ‘border security’

Former President Bill Clinton listens while participating in the Clinton Global Initiative, Tuesday, Sept. 20, 2022, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Nikhinson)

In 1996, the Republicans who had taken back control of Congress seized on immigration as a winning political issue. Party members including then-Sen. Alan Simpson (Wyo.) pushed for Congress to create an “expedited removal” system to quickly get asylum-seekers out of the country — a measure that was softened but ultimately adopted.

The deal was signed by Clinton as part of a package to avoid a government shutdown; he was essentially dared by then-Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) to either shut down the government or shut down the border.

In many ways, the IIRIRA feels like a relic of a lost age of compromise.

“There was not the kind of animosity, not the quite the political division, you see there today,” said Philip Schrag of Georgetown University, who has written a seminal book on the 1996 law.

For example, Schrag said, “there were several Republican senators, at that time, who were interested in moderating these proposals — and they were, in fact, moderated.”

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich speaks during the America First Agenda Summit, at the Marriott Marquis Hotel on July 26, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images/FILE)

But however collegial the process, the law transformed both the character of American immigration and the framing of how it was discussed.

By militarizing the U.S. border, it cut off what had once been a relatively free flow of single Mexican men seeking seasonal work — and returning home to their families for the winter — into a flow of families, as those same men realized they would not be able to return to the United States if they left their jobs there.

In prior generations, those children would have stayed in Mexico with their mothers and extended families. After 1996, hundreds of thousands came to America with their parents — where they became the group of young noncitizens later known as Dreamers.

Closing the door on refugees

The expedited removal measures in the 1996 law also marked a seminal change in how the United States treated refugees, who in subsequent years and decades would make up an increasing share of migrants, particularly as the Mexican population grew older and wealthier, driving down flows of migrants from that country.

Under the IIRIRA’s expedited removal provisions, low-level officials were given the first call on whether to deport people.

For those who made it past that step to claim asylum, it created a several-step process of screenings and enforcement — requiring heightened levels of Border Patrol troops, as well as new steps of screening interviews, credible fear interviews and court hearings.

This was of a piece with the “anti-crime, anti-terrorism and anti-immigrant” turn in the Clinton administration, Gilman said, and a major focus was means-testing: making sure no one got in free.

This was brutally controversial at the time, and human rights organizations argued that the laws would violate refugee clauses in the 1979 Refugee Act.

A 2003 study from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom argued against expedited removal on the grounds that it would lead the U.S. to kick out people who should have been allowed to stay.

And the new removal apparatus marked a dramatic shift in resources away from processing asylum claims, according to Schrag.

“Congress has starved the systems that we have for adjudicating those cases,” leading to a backup in cases that itself led to more asylum-seekers spilling across the border, the Georgetown professor said.

But beyond those spending and administrative changes, the 1996 measure marked a profound shift in how Americans thought about the problem — to being less about the status and integration of foreigners in the U.S. and more about the question of whether the border was “controlled.”

Fencing off ‘terror’ on the Rio Grande

WASHINGTON – JANUARY 23: U.S. President George W. Bush waves before the State of the Union address at the U.S. Capitol January 23, 2007 in Washington, DC. In addition to the war in Iraq, Bush was expected to touch on a wide range of topics including energy, education, immigration and health care. (Photo by Larry Downing/POOL)

In 2006, new legislation further bolstered the idea of the border as a zone in need of military control. In the aftermath of 9/11, Republicans pointed to the high numbers of labor migrants crossing the border to raise fears about terrorists coming through — though, as Massey points out, the 9/11 hijackers had all entered the country on tourist visas.

Under President George W. Bush — who, as a candidate, had deep connections to the Texas Hispanic community, and who had pushed for his own moderate immigration package that included a path to citizenship — Congress passed the Secure Fence Act in 2006.

Like the Gingrich legislation the decade before, the 2006 bill — the aftermath of a failed comprehensive immigration push from Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Edward “Ted” Kennedy (D-Mass.) — was a last-minute election year compromise package that doubled down on the idea of the border as a zone of chaos in need of barriers and well-armed law enforcement.

“They passed this act quite hurriedly in October of 2006, right on the cusp of the elections,” Doris Meissner, who ran the Immigration and Naturalization Service under Clinton, told The Hill last year.

“I think it was a political fallback at the time, and frankly, it hasn’t been taken very seriously ever since,” added Meissner, who now heads the U.S. Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute.

That bill reimagined the border for the first time as a problem — something that had to be controlled.

And it defined the ideal goal of successful “operational control” of the nearly 2,000-mile, sparsely populated, difficult terrain in far more ambitious terms than ever before.

Such control, the 2006 statute clarified, was only accomplished when the Border Patrol was able to keep anyone from crossing through.

The failure of reform

The 2006 bill wasn’t intended to be the last word on immigration policy. Congress tried in 2007 and again in 2013 to pass legislation that combined the stick of border militarization with the carrot of reforms to the legal immigration system, as well as a path to citizenship for the large populations of undocumented immigrants living “in the shadows.”

But despite backing from Bush, the 2007 bill failed in the Senate amid opposition from Republican hard-liners.

“The message is crystal-clear. The American people want us to start with enforcement at the border and at the workplace and don’t want promises,” then-Sen. David Vitter (R-La.) told The New York Times at the time.

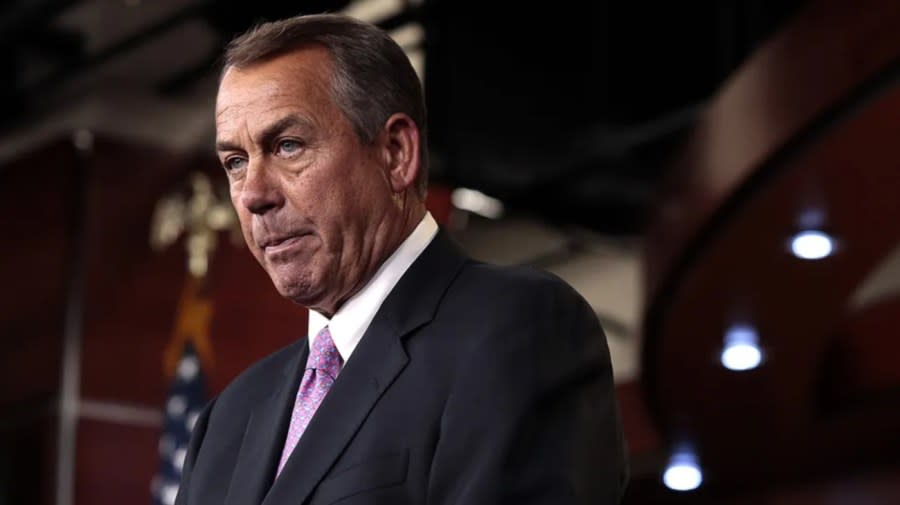

Former Speaker of the House John Boehner. (Greg Nash)

And though the 2013 bill backed by President Obama cleared the Senate 68-32, then-Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) refused to take it up amid shifting political winds. Instead, foreshadowing the dynamics in today’s House, Boehner said the lower chamber would produce its own bill, which never materialized.

That failed 2013 effort proved to be the last meaningful chance to address immigration before the character of migrant flows changed— dominated less and less by job-seeking Mexicans, whose numbers had plummeted long before Donald Trump announced his 2016 candidacy, and more by whole families seeking refuge from violence, economic collapse and the impacts of global heating back home, Massey told The Hill.

Immigration reform has also become a bigger challenge institutionally for Congress, which over the past three decades has lost most members and staffers with experience legislating the successful 1996 and 2006 reforms.

That institutional knowledge is not around in 2024, Lind said, making negotiations and their aftermath more about politics than policy.

“You have a politically charged issue where people don’t necessarily understand the details on their own enough to form an informed opinion and ask for things because of their understanding of the issues,” she said.

“Which means they’re all going to have to default to ‘Well, which is the bigger political liability for us: supporting this bill or opposing it?'”

Unlike in 1996 and 2006, even election-year pressure wasn’t enough to get the Senate’s bipartisan deal over the finish line in 2024, showcasing how much divisions on the issue have grown.

The reduction of the immigration debate to raw politics comes at a time of mass global migration.

Amid the greatest migration of refugees since the end of World War II, Congress has left border agencies few tools to efficiently process people.

This was a stark contrast to the 1970s, when the U.S. processed 1.3 million refugees from U.S.-instigated wars in Southeast Asia.

“There, we felt we had the moral obligation to process the visa, and if you look at these populations now, they’re all pretty well integrated — no problem,” Massey said.

But despite the significant role U.S. policy played in creating the violent conditions that new waves of Central American refugees sought to escape, “by the time they began showing up, we no longer had that conscience,” he said.

Doubling down on enforcement

Looking back, Gilman argued that the U.S. “would have been better with a looser system that accepted that sure, you’ll miss a few cases, but it’s for the best to let some people in who shouldn’t be here — rather than setting up entire system to avoid fraud, because the resources to fight fraud could have let you process people more quickly, and avoid problems with the backlog.”

And Massey added that this underfunding of the asylum system also led to the acceleration of the “feedback loop” in which administrative delays drive asylum-seekers across the border — creating media-friendly spectacles of mass crossings, which push policymakers to rush more border guards to the border.

This in turn drives up the number of “encounters” — a function of the fact that there are more police to count them — and further diverts money away from processing that backlog, he said.

The Senate’s latest, doomed-to-fail bill, which focused almost exclusively on enforcement and drastically reduced the ability of migrants to claim asylum — doubled down on this old pattern, Menendez said.

The senator pointed back to what he portrayed as the long arc of U.S. policy that had left the immigration system “in chaos decades after these laws were enacted.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.